Abstract

In this chapter we introduce a mathematical modeling framework based on chemical kinetics to quantitatively analyze ligand-receptor binding dynamics. Receptor-ligand interactions are represented as reversible chemical reactions, and rate equations are derived from the law of mass action for receptors with single and multiple independent binding sites. The models are expanded to incorporate cooperative binding. The equilibrium saturation fraction relating receptor binding-site occupancy to concentration, affinity, and cooperativity parameters is derived for the general cooperative case. The model provides insights into ligand binding profiles and how factors like cooperativity influence equilibrium behavior. This kinetic modeling approach offers a rigorous foundation for systematically incorporating molecular complexity to quantitatively analyze receptor-mediated cellular signaling through ligand-receptor interactions.

Introduction¶

Ligand-receptor interactions play a crucial role in many biological processes. Receptors act as signalling molecules that initiate intracellular responses upon binding to extracellular ligands. Some examples of important ligand-receptor systems include hormone-receptor interactions regulating metabolic functions, immunological reactions mediated via antigen-antibody binding, and neurotransmission via neurotransmitter receptors in the nervous system. Proper understanding of the dynamics of ligand-receptor binding is fundamental to elucidating the mechanisms of various physiological and pathological processes.

Chemical kinetics provides a powerful framework to mathematically model and analyze ligand-receptor interactions. In this chapter, we develop a kinetic framework to describe the dynamics of ligand binding to cell surface receptors. We start from the simplest case of a single ligand binding to a receptor with a single binding site. We then extend this model to account for receptors with an arbitrary number of independent binding sites. Finally, we incorporate the phenomenon of cooperativity in ligand binding to model more complex receptor systems.

In this chapter we discuss the basic concepts of chemical reactions relevant to ligand-receptor binding, introduce chemical kinetics and derivate the rate equations based on mass-action law, present kinetic models for single-site and multi-site binding and extend these models to cooperative binding.

Chemical Reactions¶

Chemical reactions describe the process of interconversion between reactants and products. Ligand-receptor binding can be regarded as a chemical reaction between the reactants, ligand () and free receptor (), converting to products bound ligand-receptor complex ().

Based on their molecular steps, chemical reactions can be categorized as elementary or non-elementary. Elementary reactions involve a single concerted reaction step where all reactants are transformed to products simultaneously. Ligand-receptor binding often approximates an elementary reaction process where the ligand directly binds to the receptor in a single step without forming any intermediate complexes.

In addition, chemical reactions can either be reversible or irreversible. The binding of ligand to receptor is generally reversible in nature, which allows the complex to dissociate back to free entities. The reaction representing ligand-receptor binding can thus be written as:

Here, the forward reaction represents ligand binding to receptor to form the complex , while the reverse reaction denotes dissociation of the complex back to free ligand and receptor. The double arrows indicate that this is a reversible process, in contrast to an irreversible reaction which only proceeds in one direction. Given these basic properties of chemical reactions, we now introduce the kinetic theory to quantitatively model ligand-receptor binding dynamics.

Chemical Kinetics Approach¶

Chemical kinetics provides a quantitative framework to study the rates of chemical reactions based on experimental observations. For elementary reactions involving single reaction steps like ligand-receptor binding, kinetics theory relies on the law of mass action.

The law of mass action states that the rate of a reaction is directly proportional to the active collision frequency of reactants. This is because for the reaction to occur, the reactant molecules must collide with sufficient energy and correct orientation for the reaction to take place. The frequency of successful collisions is directly proportional to the chance of reactants meeting. This chance is given by the product of their concentrations at the reaction site. Therefore, the reaction rate is proportional to the product of reactant concentrations.

We use square brackets () to represent the molar concentrations of species in a solution. The concentrations as opposed to amounts or numbers give an indication of how dense or dilute the reactants and products are in the reaction volume. This is important because reaction rates depend on the volume as well as amounts of substances present.

For the reversible binding reaction in Eq. (1), application of the law of mass action gives:

A reaction is said to be at chemical equilibrium when the forward and reverse reaction rates become equal, such that there is no further change in concentrations with time. At equilibrium, , which upon substitution from above leads to the relation:

where denotes molar concentration at chemical equilibrium. Parameter is known as the equilibrium or dissociation constant, and characterizes the equilibrium of the reversible binding reaction.

Modeling Ligand Binding to a Receptor with Single Binding Site¶

We consider the case where the receptor has a single binding site for ligand . The reversible binding reaction is given by Eq. (1).

Here we make two assumptions: (1) the free ligand concentration is kept constant, and (2) the total receptor concentration remains constant.

From the law of mass action, the rate equations are:

From this, we can write the rate of change of complex concentration as:

This differential equation can be solved analytically to obtain:

This solution gives the time-dependent concentration of ligand-receptor complex under the stated assumptions. The concentration of free receptors can be computed at any time as .

At steady state, the concentration becomes time-independent. Taking the time derivative to be zero gives the steady state solution:

This represents an equilibrium condition where the forward and reverse reaction rates balance each other. The fraction of receptors bound at equilibrium is given by:

The fraction of free receptors is given by

We thus obtain simple analytical expressions relating the steady state complex concentration and fraction of free and bound receptors to the system parameters like ligand concentration and kinetic rate constants.

Modeling Ligand Binding to Receptors with Multiple Independent Binding Sites¶

We extend the previous model to allow binding of multiple ligands independently to a receptor with equivalent binding sites. Let represent free receptors and the concentration of receptors with ligands bound. The general reaction scheme can be written as:

We assume the ligand can bind to any of the available sites with the same rate constants and . The factors multiplying and respectively stand for the number of empty binding sites and the number of bound ligands in each reaction.

According to the law of mass action, the net rate of formation is:

From this, the equilibrium binding equation in terms of total ligand is:

This represents a system of equations with unknowns. When completed with the conservation equation,

it can be solved to obtain steady state concentrations of all receptor states:

In particular, the fraction of free and full receptors are given by:

Extension to Cooperatively Binding Ligands¶

So far we have assumed independent, non-interacting binding of ligands to receptor sites. However, many receptor-ligand systems exhibit cooperative binding where ligand affinity increases with the occupancy of neighboring sites.

To incorporate cooperativity, we modify the binding scheme in previous section such that the dissociation constant, , of the th binding site depends on the number of ligands already bound:

The dissociation constants are defined as:

where is the cooperativity factor and is the affinity of first site.

In terms of total ligand , the equilibrium binding equations for the above reaction set are:

This represents a system of equations with unknowns. When completed with the conservation equation,

it can be solved to obtain steady state concentrations of all receptor states:

By defining the above solutions can be rewritten as

Consider the term

Notice that it is independent of when ; it equals one when and is equal to when . For all other intermediate values of , the given term is a decreasing function of that tends to zero as . From this, we can prove that

This means that, in the limit of very high cooperativity, ligand binding occurs in an “all-or-none” fashion instead of progressively as in the independent case.

Saturation Fraction, Cooperativity and the Hill Function¶

In ligand-binding experiments, the saturation fraction () is typically measured. This represents the fraction of receptor binding sites that are bound ligands. Specifically, is calculated as the ratio of total ligand-occupied binding sites to the total number of binding sites across all receptors. For receptors with binding sites that bind ligand cooperatively, can be expressed as—see Eq. (21):

When the cooperativity factor equals 1, indicating no cooperativity, Eq. (24) simplifies to:

Moreover, we have from its definition that . In other words, in this case of no cooperativity we can equivalently think of there being a concentration of single-site receptors instead of multi-site receptors. Eq. (25) then takes the well-known Michaelis-Menten form, with the property that is 0 when is 0, increases linearly at low , equals 1/2 when , and saturates to 1 as becomes very large.

In the limit of very high cooperativity (), approaches 0 for to —see Eq. (23). Therefore, Eq. (24) reduces to the equation:

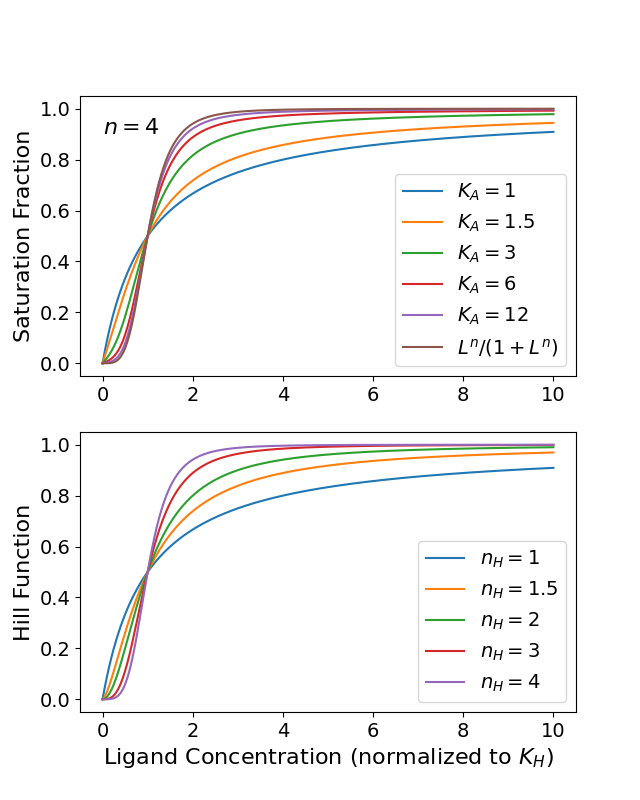

This equation resembles the Michaelis-Menten equation but has an initial zero slope and a sigmoidal shape. The steepness at , where , depends on . Large values give nearly switch-like sigmoidal behavior—see the bottom panel of Fig. Figure 1.

For finite cooperativity factors , the saturation fraction given by Eq. (24) also exhibits sigmoidal behavior as a function of ligand concentration —top panel of Fig. Figure 1. The sigmoid curve starts at the origin, reaches half-saturation where at [] = , and approaches full saturation with as becomes very large. The steepness of the sigmoid curve at the half-saturation point is determined by the magnitude of . Specifically, higher values produce steeper sigmoidal curves, indicating that ligand binding occurs in a more cooperative or concerted fashion. Thus, not only influences whether ligand binding is cooperative versus independent, but also modulates the degree of cooperativity as characterized by the steepness of the saturation fraction curve at . In summary, both the number of binding sites and the cooperativity factor help determine the switching behavior of the system in its transition from the unbound to fully bound state.

Figure 1:Top panel. Plots of the saturation fraction given by Eq. (24) For various finite cooperativity factors and the limit . Bottom panel. Plots of the Hill function with growing Hill exponents up to .

The British physiologist A.V. Hill recognized that varying a single parameter in his equation could qualitatively replicate the effects of changing the cooperativity factor from one to infinity. Specifically, he proposed the equation (now bearing his name):

where is a new parameter that can be continuously varied between 0 and the maximum number of binding sites per receptor, . Just as increasing made the binding curve steeper, larger values also produce a sharper sigmoidal shape. Therefore, the Hill equation captures the essence of cooperative binding through a single tunable exponent rather than two separate parameters ( and ).

This elegantly simplified description proved invaluable for analyzing ligand-binding data. By fitting experimental saturation fractions to the Hill equation, the degree of cooperativity could be estimated from a single parameter, . Since its introduction, the Hill equation has become widely adopted for modeling systems exhibiting sigmoidal saturation behavior, including cooperative ligand-receptor interactions and many other biological switch-like responses. Its popularity stems from providing a tractable phenomenological description of cooperativity using a single cooperativity index.

Discussion¶

In this chapter, we developed a kinetic framework to quantitatively model the binding dynamics of ligands to cell surface receptors. Starting from the basic concepts of chemical reactions and kinetics, we derived reaction-rate equations based on the law of mass action.

We first considered a single ligand binding reversibly to receptors with one or multiple independent binding sites. The corresponding reaction schemes led to systems of ordinary differential equations describing changes in species concentrations over time. Analytical solutions were obtained for the single site case under specific assumptions. We then extended the independent binding model to incorporate cooperativity between ligand-binding sites. The affinity of subsequent binding was made dependent on the number of sites already occupied.

The saturation fraction was derived for the general cooperative case in terms of system parameters like ligand concentration, affinity constants and cooperativity factor. This quantity characterizes the fraction of receptors that are fully ligand-bound at equilibrium. The obtained results provided quantitative insights into how ligand occupancy is influenced by biochemical parameters like cooperativity.

In summary, chemical kinetics provides a rigorous mathematical framework for analyzing ligand-receptor interactions, which form the basis of many cellular signaling pathways. Future work could involve applying these models to specific biological systems and experimentally validating model assumptions and parameters. Extensions may also account for ligand depletion, receptor heterogeneity and conformational changes.